Foreword

Death is a part of life, and has always been unavoidable and frightening. What awaits us after death is a mystery. The beliefs and rituals that helped people come to terms with death in the ancient world may seem strange to us now, but we understand the emotions they express. Ancient places and artefacts link us to the people of the distant past and remind us of our own mortality.

Life and death are interwoven, and the ways people lived are reflected in the burial customs they used. A great many of the archaeological finds from the Mediterranean area that make up our museum collections, come from graves and cemeteries – sarcophagi, urns and other burial containers, grave stones, inscriptions and grave gifts – and provide us with important insights into the lives, traditions and beliefs of the people of the Classical World.

The collections of Classical Antiquites in Oslo contain a wealth of grave art and burial goods from different ancient periods and cultures. Our main focus is on the Greek and Roman periods, but we have traced the long lines back to Ancient Egypt and forward to early Byzantium, a period from roughly 600 BC to 600 AD. These rich and varied burial traditions reflect the diverse and complex world of Classical Antiquity, which despite the two thousand years that have passed, has much in common with our own.

Most of the objects on display in our exhibition come from the Museum of Cultural History’s own collections, including the important collection of Baron von Ustinow from Palestine. We are also grateful to the National Museum for Art, Architecture and Design and to the Astrup family for their generous loans. Many of the objects have never been previously exhibited and some have never been published. Dead Classic provides us with an exciting opportunity to bring these cultural treasures out of the valley of the shadows and into the light.

Tomb raiders and treasure hunters

The ruins of the ancient cities and buildings of the Classical World often remained visible for centuries, although local people probably stripped the sites soon after they were abandoned. Graves and tombs, on the other hand, were often underground or otherwise hidden, and thus difficult to locate and loot. Discovering graves has universal appeal and the prospect of uncovering treasures and hidden secrets has always attracted treasure hunters, whether they were seeking riches, adventure, or scientific knowledge.

In earlier times grave robbers and tomb raiders were mainly looking for precious metals they could melt down and reuse. Seemingly worthless material such as bone and pottery was thrown away. With the renewed interest in ancient art in the Renaissance, treasure hunting found a new objective - to recover and amass valuable objects of art. Increasing demand made the art trade a lucrative business and a huge numbers of grave goods and funerary art found their way into private and public collections. In the modern era, objects have been recovered as the result of systematic archaeological excavations.

The objects displayed in Dead Classic have come to us in a variety of ways and reflect the changing history of collecting. Some objects were unearthed accidentally by farmers or construction workers. Others were unearthed through professional archaeological investigations. Most have been purchased or donated through legal channels, though many may once have been the booty of professional tomb raiders, acquired at a time before the trade in stolen cultural property was banned. All have a story to tell.

The Mediterranean in Antiquity

Classical antiquity is usually defined as the period from 500 BC to AD 500, when Greek and Roman culture dominated the lands around the Mediterranean Sea.

The Arcaic period (750 – 480 BC) Greeks began to settle along the coasts of southern Italy, Sicily, Libya, southern France, Spain and the Black Sea. The Greeks were strongly influenced by the Eastern cultures of Mesopotamia, Asia Minor and Egypt, and were to have a massive cultural impact on the near East, southern Europe and northern Africa.

In the Classical period (480-330 BC) The Greeks reached an unprecedented level of artistic and science. Athens was the centre of philosophy, politics, literature and architecture.

Hellenistic period (330 – 30 BC) Greek influence spread throughout the Mediterranean world where it blended with local traditions. With the conquests of Alexander the Great (336-323 BC), Greek influence reached as Persia and India.

The Roman Republic (509-31 BC) The Romans extended their power over their neighbours- the Italic people and the Etruscans - and then over more and more of the Mediterranean world. They defeated their greatest rivals, the Phoenicians, and large parts of the Greek east came under Roman control. In 146 BC the Romans destroyed the Greek city of Corinth and the Phoenician capital of Carthage. The art they brought back as war booty helped to bring Greek taste and fashion to Rome.

The Roman Empire (31 BC - 395 AD) At its height, the Roman Empire extended from Mesopotamia to Morocco and from Britain to southern Egypt. The Romans were tolerant of most of the religions they encountered, and absorbed traditions from the people they conquered. Roman art was strongly influenced by Egyptian, Etruscan and Greek art.

Late Antiquity (300 – 650 AD) Under the Emperor Constantine the Great (312-337 AD), Christianity became the accepted state religion of the Roman Empire. In 395 AD, the Empire was divided into an eastern and a western part. The Western Empire was invaded by Germanic tribes and finally came under their control in 476 AD. The Eastern, or Byzantine Empire, was significantly reduced in the early 600’s when Palestine, Syria and Egypt fell to the Arabs. This usually marks the end of Classical Antiquity.

Life in classical times

Peasants, pedagogues and politicians

Like us, the Greeks and Romans lived on farms, in villages or in cities, although most people lived in the countryside. They were governed by politicians, and the concept of democracy, was first formulated in ancient Greece. There were, however, periods when power was held by one, or a handful of men. Best known is Julius Caesar, the man who defied the Senate of Rome and ended the Republic, and his successor Caesar Augustus.

The citizens of Athens and Rome were passionate about politics, and crowded public squares such as the Athenian Agora and the Forum Romanum, were often the scenes of lively discussions. In Athens, the Agora was surrounded by stoas where citizens could talk under shady porticos. Here philosophers held classes for the city’s children and youths. Among the most famous were Socrates (c 470-399 BC), Plato (c 428-348 BC) and Aristotle (384-322 BC).

In Rome, the Forum was crossed by the Via Sacra, where victorious generals paraded under magnificent painted arches on their return from successful campaigns. At the end of the Via Sacra, beneath Capitol Hill, lay the Curia, where important decrees were made, and the Rostra, the speakers’ platform. Lining the road were basilicas with colonnades where citizens met to gossip and discuss politics. These were also popular pursuits at the Roman baths, the thermae. The baths were large, and in most cases, public buildings. A visit to the bath was an important part of Roman life, not only to wash, but also as a way of passing time and socialising. From the written sources we know that people often went to the baths to people-watch, and the graffiti on the walls are often rude comments about other guests.

Athletes, actors, gladiators and charioteers

Sport was very important and people believed in the connection between a healthy body and a healthy mind. Sports such as wrestling and discus throwing, took place in arenas located at the gymnasia where young men went to exercise and compete.

In Athens and Rome, as well as in all major cities of the Classical World, there were theatres where actors and actresses performed comedies and tragedies. The audiences were seated on ascending semi-circular rows around a centre stage. This ensured that the actor’s could be clearly heard throughout the theatre.

Amphitheatres - the most famous of which was the Colosseum - were found in all larger Roman cities. Here gladiators fought each other and also against wild animals brought from all corners of the Empire. At the opening of the Colosseum in 80 AD, 9,000 animals were slaughtered for the amusement of the people. When the Emperor Trajan (AD 98-117) celebrated a victory over the Germans, 110 animals were killed each day over a period of 100 days, a total of 11 000 animals.

The gladiators fought to survive. The only way to leave the arena alive was by winning. Those who succeeded were enormously popular, and can be compared to modern pop idols and football stars.

Chariot racing, another hugely popular spectator sport, took place in specially-built stadiums. In Rome, chariot racing was closely linked to politics, and the various factions had their own chariots, marked with the party colours. Wealthy citizens with political ambitions often sponsored the chariots.

Honouring the Gods

The most important buildings in any ancient city were the temples, the sacred buildings where people worshiped their gods. The desire to please the gods was felt everywhere in ancient society and the gods were present in all parts of public life. Statues and altars were set at crossroads and in private houses as well as in temples. There were twelve main gods in the Greek pantheon. The Romans inherited the Greek gods and gave them Latin names.

In addition to these twelve gods, there were various half-gods, heroes and mythological figures such as water nymphs, the half-horse-half-man centaurs, and the half-goat-half-man satyrs. The many myths about the gods can be compared to legends and fairytales, but they always had an edge and there was always a lesson to be learned. Myths told people about what would happen if they neglected the gods or did not obey them. Most classical myths deal with the relationship between gods and humans, and death is often major theme.

In order to appease the gods, people made sacrifices at shrines and altars, and took part in religious festivals which were celebrated throughout the year. In both Greece and Rome politics and religion were interwoven and the festivals were often sponsored by rich patrons. In Greece, festivals were often connected with sporting events, such as the Olympic and the Panathenaic games. Theatrical performances and games were also part of these festivals, some of which lasted for several days.

In Rome, the gods were celebrated at festivals held on special dates, and there were more red-letter days in the Roman calendar than in ours. Many of these festivals grew out of earlier traditions based on nature worship, such as offering gifts to mark the arrival of the different seasons. One of these, the feast of the fertility god Dionysus-Bacchus which took place in the spring, was especially wild and ecstatic. In addition to the fixed calendar of festivals, some emperors added new feasts and fairs suited to their tastes and budget.

Senators and slaves

Rich Romans held dinner parties sometimes lasting all night, where huge amounts of food and wine were consumed in elegant dining rooms. Food and wine was imported from various parts of the Mediterranean. Wine and other liquids were transported by ship in large ceramic jars (amphora).

People ate while in a reclining position on couches in the dining room or in the atrium. Musicians and dancers entertained the guests who wore expensive clothes, jewels and exotic perfume. While most people’s diet consisted mainly of bread, porridge or cabbage supplemented with meat or fish when possible, the food served at the banquets of the upper class was often extravagant, even by modern gourmet standards. Delicacies such as mussels and various cheeses were often imported from great distances. At the banquets, slaves served the food and attended to the guest’s needs.

Life as a slave could range from being tolerable to miserable. Slaves who had special skills such as bakers, blacksmiths and artists were often appreciated for their usefulness and treated with consideration. Other slaves had to live with the farm animals and were given meagre portions of leftovers to eat. In Roman times, slaves could be set free by their masters, or they could try to save enough money to buy their freedom. Freed slaves could marry, have families and start their own business, but they would never be counted as freeborn Roman citizens. This would have to wait until the next generation. People’s status as freed slaves or freeborn citizens, was displayed in various ways, such as by the type of ring they wore. In death, a person’s status was inscribed on their grave stone.

Her husband's property

The differences between the sexes were profound. Men and women had different duties and rights, and these were reflected in the layout of ancient houses. Large parts of the house were reserved for female activities connected to running the house, while the male zone was in the more public areas near the entrance where the master could receive visitors. This reflects the belief that a woman’s place was in the home with the family, while the man was outgoing and engaged in society. The Greeks seem to have held to this social order more rigidly than the Romans.

In Greece, a proper wife was not supposed to leave the house unless it was to take part in religious activities. A Roman wife, however, could move around quite freely although she had to keep her head covered. In both societies, a wife was considered to be her husband’s property and if she was caught committing adultery he had the right to kill her. One famous example of a woman who met such an end is Messalina, the wife of Emperor Claudius. She went as far as marrying another man while she was still married to the emperor.

Children were known to be the result of sexual intercourse, but exactly how fertilisation took place was not fully understood. Monogamy was a way of ensuring controlled paternity. In Rome, however, adopted children had the same rights as biological offspring.

Women from the upper levels of society were sometimes able to achieve a considerable degree of independence. This was especially true of women who realized that their marriages were fundamentally political alliances, and could exploit their economic importance. Other women, such as Nero’s mother Agrippina Minor, wielded influence through their children.

Although strong and colourful women like Cleopatra have always attracted attention, life for the average woman in Greece and Rome was a perilous journey. Girls became mothers as young as twelve, and more women died during child-birth than men were killed in battle.

Soldiers and sailors

The Romans had an army and a navy, and the Roman military was probably the best organised in the history of warfare. The army consisted of legions made up of Roman infantry, and auxiliary troops made up of non-Roman allies. A legion was normally accompanied by auxiliary troops, which were summoned when needed. There were around 4200 legions during the Republican period and 5500 in the time of the Empire. Each legion and cohort was given a name, such as Cohors III Alpinorum.

The military success of Rome is often attributed to the efficiency of the legions. In addition to their far-reaching conquests, Roman soldiers were responsible for the construction of roads all over the Empire. The army was thus a sound investment, but an expensive one.

The soldier’s themselves were not paid much, and military service could last for years. Soldiers often never returned to their place of origin, but as veterans, settled in the colonies where they were given land. By the end of the 2nd century AD, it was legal for soldiers to marry women in the provinces, and many of them settled and mixed with the local population. The greatest reason why soldiers never returned home was that so many died in military service. The many tombstones commemorating fallen soldiers attest to this.

Mare nostrum

The Mediterranean Sea is of inestimable importance for our understanding of the world of Classical Antiquity. It was the sea that made it possible for armies to travel quickly and conquer vast areas, and it was the sea that enabled merchants to transport the vast array of goods between port cities.

The Greeks colonised large parts of the Mediterranean, and its seaports supplied the mother city-states with goods and produce. For Rome, however, the Mediterranean was its very lifeline. Without grain from Sicily and North Africa, Rome could never have fed nearly a million inhabitants. Along with the goods from all corners of the world came a wealth of new ideas and impulses. Foreign merchants and slaves came with their traditions, religions and cultural traits. Soldiers returned from service abroad with new experiences, stories and outlooks.

Many foreign deities found their way into Roman mythology. The various new cultural currents gradually changed and enriched Roman culture and produced a complexity which is mirrored in matters pertaining to death, such as burial customs.

A watery grave

The Mediterranean was a busy sea and maritime traffic was intense. No matter how experienced the crew, sudden storms and other disasters caused frequent shipwrecks. Neptune (Gr. Poseidon), god of the seas, and Mercury (Gr. Hermes), protector of merchants, were worshipped in port cities in hope of protecting travellers from the perils of the sea and saving them from a restless watery grave.

Many written sources tell of life and death at sea, in peacetime as well as in war. The Greek poet Archilochos, writing in the 7th century BC, extols, “Let us hide the sad gifts which Poseidon brings.” (Frg. 53). The sad gifts are the corpses of the drowned.

Burial customs simplified

Simplified timeline showing burial customs (including northern Europe)

| North Europe | Neolithic Period à 1800 BC |

Inhumation in low, small burial mounds |

| Early Bronze Age 1800 - 1000 BC | Inhumation in large burial mounds | |

| Late Bronze Age 1000 - 500 BC | Cremation remains in urns in burial mounds | |

|

Early Iron Age 500 BC - 0 |

Simple cremation | |

| Middle Iron Age 0 - 300 AD | Inhumation | |

| Late Iron Age 300 - 400 AD | Cremation | |

| Migration Period 400 - 800 AD | Central and northern Norway: inhumation Rest of northern Europe: cremation |

|

| Egypt | 3000 BC - 200 AD | Mummy coffins in burial chambers |

| Mesopotamia | C 3000 - 2000 BC | Simple inhumation burials in pits and early stone sarcophagi |

| C 2000 - 1500 BC |

Simple pit burials, ceramic sarcophagi, |

|

| Greece | Archaic period 7th - 6th centuries BC |

Cinerary urns buried and marked out with stelae |

| Classical period 5th - 4th centuries BC | Cinerary urns buried and marked out with stelae | |

| Hellenistic period 4th - 1st centuries BC | Sarcophagi | |

| Etruria | Archaic and Classical period 6th - 5th centuries BC |

Cinerary urns, inhumation and some sarcophagi in tumuli |

| Hellenistic period 4th - 1st centuries BC | Sarcophagi in tumuli | |

| Rome | Archaic period 7th - 4th centuries BC | Cinerary urns, buried |

| Republican Rome 4th - 1st centuries BC | Cinerary urns, buried | |

| Early Imperial Rome late 1st century BC - 2nd century AD |

Cinerary urns in columbaria, grave houses, buried under stelae or in monuments |

|

| Middle and Later Imperial Rome 2nd - 3rd centuries AD | Inhumation, sarcophagi in grave houses | |

| Late Antiquity 4th century AD | Sarcophagi in grave houses | |

| Early Christian Rome 3rd - 6th centuries AD |

Inhumation, sarcophagi in catacombs |

Simplified timeline showing creamtion and inhumation practices

| NORTH EUROPE | EGYPT | GREECE | ROMAN EMPIRE | ||||

| Cremation | Inhumation | Inhumation | Cremation | Inhumation | Cremation | Inhumation | |

| 2000 BC | Urns in burial mounds | Large burial mounds | Cremation, grave stelae |

Cremation | |||

| 1000 BC | |||||||

| 700 BC | |||||||

| 600 BC | |||||||

| 500 BC | Simple cremation graves | ||||||

| 400 BC | |||||||

| 300 BC | |||||||

| 200 BC | Sarchophagi | ||||||

| 100 BC | Simple graves | ||||||

| 0 | Sarcophagi | ||||||

| 100 AD | |||||||

| 200AD | |||||||

| 300 AD | The rest of Northern-Europe |

Central- and northern Norway |

|||||

| 400 AD | |||||||

| 500 AD | Coffins | ||||||

Coffins and sarcophagi in many shades and sizes

The word sarcophagus comes from the Greek word σαρκοφάγος, meaning “eater of flesh” (from sarx - flesh, and phagô – to eat). Later, probably around the 2nd century AD, the word came to mean a stone coffin. Pliny the Elder gives an explanation for this macabre word: “At Assos in Troas, there is found a stone of a laminated texture, called sarcophagus. It is a well-known fact, that dead bodies, when buried in this stone, are consumed in the course of forty days, with the sole exception of the teeth” (Pliny, NH 2, 210).

Early sarcophagi

Coffins and sarcophagi were standard inventory in Egyptian tombs from about 3000 BC to the Roman era. In the course of more than 3000 years, coffins went through considerable changes in size, shape, form, decoration, materials and function. Two of the most significant innovations were the introduction of the anthropoid, or human shaped coffin towards the end of the Middle Kingdom (c 2055-1650 BC), and the custom of including several coffins in one burial, stacked inside one another like Russian Matroyska dolls (foto av C47709). The fashion for anthropoid sarcophagi spread from Egypt to the Near East by the second half of the 2nd millennium BC.

Early Greek sarcophagi

In Greece, smaller stone or clay chests - larnakes - which held inhumation burials in a contracted position, were used in the 2nd millennium BC. These were in use until the early 1st millennium when cists constructed of stone slabs became common. In the 7th century BC real stone sarcophagi, which allowed for a burial in outstretched position, came into use in Corinth. During the 7th and the 6th century BC, sarcophagi of stone, terracotta and wood were produced in other places in the Greek world, particularly the eastern islands of the Aegean and Cyprus. One of the first production centres of sarcophagi in the Greek world was the town of Clazomenai, now Urla, on the western coast of Turkey, some 30 km west of Izmir. Our outstanding example dates from about 580-540 BC, and is among the earliest types of decorated sarcophagi to be used in the Greek world.

Later Greek sarcophagi

In the Classical Greek period sarcophagi were replaced by cremation graves marked by grave stelae. Around 300 BC, at the time of Alexander the Great, a new and elaborate type of sarcophagi appears in the Hellenistic world. The Hellenistic sarcophagi are generally large, and decorated with mythological motives. They have the shape of a house, and the lids resemble the roof of a temple.

Etruscan sarcophagi

The Etruscans used sarcophagi for their burials during the 7th century BC, but examples surviving from this early period are rare. In the 6th century BC the numbers increase, and terracotta coffins with steep lid sides resembling roofs became common. This kind of sarcophagus was decorated with figures, usually lions and panthers. Popular motifs also include banquets, battles, funerary and mythological scenes. Cinerary urns for cremations burials were also in use. The lids of the urns were often decorated with the deceased couple seated on the top of the lid. From the 4th century BC onwards, Etruscan sarcophagi of terracotta and stone were mass produced, and used to house cinerary urns.

Roman sarcophagi

The Romans cremated their dead until the first decades of the 2nd century AD, when sarcophagi gradually became more common. The earliest Roman sarcophagi were inspired by Greek-Hellenistic examples. They have frontal panels covered with mythological figures or battle scenes. From the later half of the 2nd century and throughout the 3rd century AD, ornamentation becomes more detailed and elaborate. Battle scenes dominate, but mythological scenes and motifs from daily life become more frequent. In the second half of the 3rd century AD ornamentation on the sarcophagi becomes simpler, often a clipeus or shield on the front flanked by vertical wave patterns.

Late antique and early Christian sarcophagi

During the 4th century AD the sculpture on the Roman sarcophagi becomes more stylistic. When Christianity became the accepted state religion, neutral or ambiguous motifs became more common, such as the winged figures representing apostles and good shepherds.

Life after death

Beliefs about death and the afterlife

Hermes, the Helper, led them down the dank ways. Past the streams of Oceanus they went, past the rock Leucas, past the gates of the sun and the land of dreams, and quickly came to the mead of asphodel, where the spirits dwell, phantoms of men who have done with toils.

– Homer, Odyssey 24.10-14.

What awaits us on the other side? This question occupied the thoughts of Greeks and the Romans. They believed they would be guided by Hermes, the messenger of the gods, and that he would take them to a river, the Styx, which they had to cross with the help of Charon, the ferryman who conveyed the dead to the shore of Hades, the Underworld. The dead were expected to “pay the ferryman” (Charon’s coin). The gates to the Underworld were guarded by Cerberos, a three-headed dog. The Greek underworld was called Hades after the god of death, who resides in his realm together with his wife Persephone. They determine the fate of the dead in the Afterlife.

There are several versions of what happens to the “soul” (psyché) after death. In early versions, the ghosts of the dead wander the plains of Hades in an endless state of oblivion, unaware of events on earth. A special fate awaited those who had not been given a proper burial. They were denied admission to Hades and had to roam outside the Underworld, sometimes haunting the places of the living as ghosts. This thought so terrified the Greeks that they even allowed their enemies to bury their dead after battle.

The Roman poet Virgil gives us a detailed description of the topography of the Underworld. It is divided into three parts. The first is Limbo. Here dwell all those who have died prematurely of love or suicide, those who have been wrongfully sentenced, and those who have died as warriors or as children. After passing Limbo, the road divides; the left leads down to Tartarus, where the wrong-doers suffer their tortures, and the right leads up to the Golden Palace of Hades, where the blessed enjoy eternal feasting and singing.

The popular perception of the Underworld was much less elaborate. The traditional view was that the souls of the dead lived somewhere under the earth; in a grave, or some other kind of underground room. For the more optimistic, there were other places the ”soul” could go. Homer describes a wonderful place called Elysium, where great heroes went when they died. In time, Elysium became a haven for all those the gods favoured. It was often called the Island of the Blessed and was said to lie somewhere beyond the Ocean. Others believed the ghosts of the dead travelled to the stars.

Mystery religions and philosophy

Mystery religions offered the promise of a brighter Afterlife. By passing initiation rites, a person was sworn into the secret mysteries of a special deity. For example, people initiated in the Dionysian mysteries had special knowledge that could improve their chances of receiving a favourable judgement on the day of reckoning. They knew to place golden leaves in their graves with inscriptions recommending them to Persephone, the more sympathetic of the judging deities of Hades.

Nevertheless, there was no lack of sceptics, or even those who denied the immortality of the soul. The philosopher Epicurus (c 342 -271 BC) and his followers were convinced that there was no form of existence after death. Epicurus wrote: “Death, therefore, the most awful of evils, is nothing to us, seeing that, when we are, death is not come, and, when death is come, we are not.” (Letter to Menoikeus)

Communication between the living and the dead

Many places around the Mediterranean, especially lakes and caves, were thought to be entrances to the Underworld. These were seen as passages connecting the World of the Living with the Underworld which made communication between the living and the dead possible, at least for those who had special knowledge, or help from the gods.

The living could contact the dead directly by means of special rituals. The “souls” of the dead, however, first had to be strengthened, and this could be done by feeding them the blood of sacrificed animals. There are stories of how heroes entered the Underworld in order to get information, or to free a ”soul” from Hades. The latter was usually a fruitless effort, since Death could only be cheated in the short term.

Classical literature contains plenty of ghost stories. There were many superstitious beliefs about helpful spirits and the restless dead who would visit the living with the purpose of doing good or evil. There are also examples of living individuals who sought their loved ones in Hades. The tale of Orpheus, who went in search of Eurydice, is well known.

Burying the dead

How the Greeks buried their dead

We will never know exactly how burial rites were practiced in ancient Greece and practices undoubtedly varied. Certain common features, however, can be established using archaeological and written evidence.

After death, the eyes and mouth were closed and the body was washed, anointed and wrapped in a shroud. It was then placed on a bier, usually a couch (kline´) with its feet to the door. The corpse lay on a bed of vine, myrtle and laurel leaves. Ointment flasks (lekythoi) were placed by the bier and ribbons and wreaths of laurel and celery decorated both the body and the surrounding walls.

Those who visited the corpse purified themselves afterwards with water. Women sang and lamented, while men mourned at the bier.

The procession to the grave usually took place on the third day after death. The body, still resting on the kliné, was either carried, or drawn on a cart. Men walked in front of the body, women behind it, and the procession could be accompanied by flute players.

At the grave, the body was either burnt on a pyre or buried . After cremation, the bones and ashes were collected and placed in an urn. Grave goods could be burnt along with the body and were sometimes deliberately broken. These were placed in or on the grave or in special trenches nearby. Offerings were made by the mourners, accompanied with prayers. Offerings could be extensive, and included milk, honey, celery, water, wine and fruit. The ground was soaked with the blood of sacrificed animals - sheep, lambs, goats, fowl and sometimes bulls, in order to appease the dead.

Purification rituals followed the burial, and a banquet, the perideipnon, was held in the home of the deceased. Offering rites were held at the grave on the third and ninth day after death (or burial) and again on the thirtieth day . This marked the end of the official period of mourning. The family also made offerings on the anniversary of the death and at the annual festival for the dead, the genesia.

Greek necropolises

Necropolis literally means “city of the dead,” but is used as a general term for burial sites in both Ancient Egypt and the ancient Mediterranean world before the introduction of Christianity.

Originally Greeks buried their dead near their houses, but as towns developed, cemeteries were moved outside the city walls where they extended along the major roads leading out of the city. The necropolises of Athens, such as the well-known Kerameikos, consisted of small compartments for use by a family or burial collegium. Relief- and inscription slabs, marble vases and small columns were erected to honour the dead. Other regions followed other traditions. In eastern Greek Asia Minor (today’s western Turkey) for example, rock-hewn tombs used for multiple burials were very common.

Actual tomb monuments were less common in the Greek world before the Roman era. Yet the giant temple-like tomb of King Mausollos, in Halikarnassos (Bodrum), was considered one of the wonders of the ancient world and gave its name to the term mausoleum.

Necropolises were not only used for burials and burial rites, such as cremation, but were also the scene of remembrance ceremonies and offerings. In fact, necropolises may have been very lively places during certain festivals, such as the genesia.

Greek grave monuments

Grave relief slabs and stelae were the most common types of grave markers in Greek necropolises between the 6th century BC and Roman times. They could be standing stones, so-called stelae, comparable to modern tombstones, or grave markers attached to some sort of a frame or construction. In some parts of the Greek world, reliefs were carved directly into the rock face at the site of the tomb. The grave reliefs of classical Athens were considered the ideal and were copied and imitated all over the Greek world. The grave reliefs in our exhibition all date to the Hellenistic period.

Grave reliefs often depict banquet scenes showing the deceased dining in splendor in his opulent home, thus providing the opportunity to display the family’s wealth. These banquet scenes were very common in Asia Minor and imitate classical “hero cult motifs“ from Athens. The deceased is often seen feasting on a couch with his family and servants gathered around him.

Another typical motif shows two people holding hands. These have been interpreted as departure scenes where the deceased bids farewell to a friend or relative before the journey to the underworld.

Gatherings of the deceased and his relatives can involve a large group of people if a whole family is depicted.

The hero cult

The Greeks had a long tradition of worshipping mythological warriors or city founders at their actual or legendary graves. In time, the hero cult was extended to include political and military leaders, and other celebrities. While the cult of the ancestors was a private family affair, the hero cult had a more public and official character. Worshippers brought votive offerings, usually food and drink, to the sanctuaries. Many of the surviving votive reliefs show one or more heroes at a banquet, feasting on the everlasting gifts of the worshippers.

The Roman way of death

At the time of the Emperor Augustus (27 BC-14 AD), Rome had and 800 000 – 1 000 000 inhabitants. Of these, around 30 000 people died every year, an average of over 80 deaths a day. When there were epidemics, the daily death toll may have risen to the thousands. By 300 AD, there were probably several million burials in the outskirts of Rome alone. And Rome was only one of many cities in the Empire. There must have been tens of millions of graves throughout the Mediterranean region.

We know very little about how poorer Romans regarded death or how they were buried. Most of the information we have about Roman burial customs pertains to the city’s more prosperous citizens.

The Last Kiss – Preparing the Body

The family gathered by the death-bed and the nearest relative gave the last kiss, or rather caught the last breath of the deceased. The eyes were then closed and the family began their lamentations and called out the deceased’s name. The body was washed, anointed and sometimes garlanded with a wreath. A coin might be placed in the deceased’s mouth, as the fare for the ferryman.

The deceased was then laid out on a bed in the central hall of the house (atrium), with the feet towards the entrance. A pine or cypress branch was fixed over the entrance door to indicate that a death had occurred. To show their bereavement, the family members rubbed ashes on their faces and wore dark mourning clothes.

The funeral procession was made up of the family and, depending on their wealth, of servants, professional mourners and musicians with flutes and horns. Although funerals did not usually take place at night, torches and candles played an important part in the ceremony, and were probably used as “magic” to ward off evil. At the burial site, gravediggers prepared the tomb and a funeral service was held in honour of the deceased.

The funeral of a famous or important Roman was often a major public event. The historian Polybius gives us an account:

Whenever one of their illustrious men dies, in the course of his funeral, the body with all its paraphernalia is carried into the forum to the Rostra, as a raised platform there is called, and sometimes is propped upright upon it so as to be conspicuous, or, more rarely, is laid upon it. Then with all the people standing round, his son, if he has left one of full age and he is there, or, failing him, one of his relations, mounts the Rostra, and delivers a speech concerning the virtues of the deceased, and the successful exploits performed by him in his lifetime.

– Histories 6, 53

We even hear that actors, dressed up in the deceased’s cloths and wearing masks with his facial features, would mimic the dead person, sometimes in a comic or mocking way.

Earth and Fire - Inhumation and Cremation

The Romans practiced both inhumation (burying of the body) and cremation (burning the body). Cremation was almost exclusively used between the 2nd century BC and the beginning of the 2nd century AD. After that, inhumation became increasingly popular, replacing cremation completely by Christian times.

In cremations, the body was burnt on a special platform for the pyre, or at the actual site of the grave. The family gathered the bones and ashes of the dead and placed them in a funerary urn. The urn was then placed on a shelf in the tomb chamber or in a grave dug into the earth. During the burial rites, offerings were made to the dead. Usually people were cremated as quickly as possible, as the warm climate caused rapid decomposition. In some cases, however, it could take days to prepare the ceremony.

The technical definition of being dead was not as scientific as it is today, and it occasionally happened that people woke up before the fires were lit. Pliny (NH 7.173) tells a story about a certain Acilius Ariolas, who had been considered dead for some days when he was woken by the heat of the pyre. Unfortunately his family had returned to their home, and the slave who was left to watch the fire was not able to extinguish it on his own.

The most common type of grave house was the columbarium, where cinerary urns were placed in small alcoves on shelves, similar to those inside a dovecote, hence the name. The columbaria held the urns of a group of people; for example a family and their relatives, or a family’s slaves. Sometimes they were owned by a collegium, an association that provided for the funeral and burial place of its members. The columbaria sometimes had cooking facilities and dining couches, for the feasts that were regularly held there during the year. These tombs often had their own ustrinum, the place for the pyre.

Purification and Feast

The Romans considered death to be unclean. When a family member died the whole household had to undergo a purification ritual with water and fire. On the day of the burial a funeral feast took place. It marked the beginning of a longer purification period usually lasting until the ninth day after death. At this time the mourning family and their close friends held another feast at the tomb to honour the deceased. In an account by the writer Petronius, the stone-mason Habinnas describes a cena novendialis to his friend Trimalchio:

Already drunk and wearing several wreaths, his (Habinnas) forehead smeared with perfume which ran down into his eyes, he advanced with his hands upon his wife's shoulders,…(Trimalchio) asked him….., how he had been entertained. "We had everything except yourself, for my heart and soul were here, but it was fine, it was, by Hercules. Scissa was giving a Novendial feast for her slave, whom she freed on his death-bed, …, but everything went off well, even if we did have to pour half our wine on the bones of the late lamented .

– Satyricon 10, 65

The urn of the deceased slave must have stood among the mourners, who toasted him and then offered him part of their wine by pouring it over his ashes. Habinnas then goes on to give a detailed account of the sumptuous food they were served, evidence that feasts were held at the tomb.

Grief

The sorrow and grief people feel when they loose someone dear to them has been the same throughout time. When reading written accounts and grave inscriptions, we can easily identify with those in mourning.

Two Roman writers Romans Catullus and Juvenal, known for their sharp tongues and pens, evoke our sympathy when torn apart by sorrow at the death of their loved ones. We sympathise with Catullus on the loss of his brother, and with Martial, who has lost his daughter:

Today we give to the earth the body of my little girl,

my little darling; no more will she swirl

around the house in her own strange, impenetrable games

or pout, or kick, or scream, or whine our name

in that annoying tone we tried to cure her of before

and now would give anything to hear once more.

She'll find whatever it is one finds when this bright life ends –

eternal silence or the souls of friends.

For what it's worth, we'll bow our heads and try what prayer can do

lie lightly, earth -- she stepped so lightly on you.

The Roman poet Ovid expresses his mixed emotions of sorrow and anger at his girlfriend Corinna when she almost dies after inducing an abortion (Ovid Amores 14-15). He worries for her life, while at the same time blaming her for having killed their baby. In an earlier verse of the same poem he describes their mourning of Corinna’s dead parrot, even citing the inscription on the grave stone.

Food and Spirits – Remembering the Dead

The Greeks and the Romans continued to remember their dead after the funeral. The birthday of the deceased, dies natalis, was a time to visit the grave and celebrate with a feast. Cooking facilities and dining couches, triclinia, have been found at the tombs, or in special houses at the grave sites. Other occasions were more general, public days of remembrance, like our All Saints Day or Memorial Day in the USA.

The Romans believed in various kinds of ghosts, or spirits which were thought to be the “shadows” of people who had died. The most important, the manes and the lemurs, were celebrated with festivals. The manes were generally benevolent, while the lemures were restless and could return to haunt the living.

The Parentalia (13th- 24th of February) was a festival honouring parents and the family. During this festival, sacrifices were made at the tombs to appease the spirits of the ancestors (manes). Libation offerings of water, wine, milk, honey, or perfumes were poured onto the grave, over the ashes in the urns, or even through pipes into the graves. Bread, cakes, grapes, sausages, incense or fruits, were also frequently sacrificed. Lamps too were lit on special occasions. Terrible things happened to those who neglected the parentalia,”The ghost came moaning from their tombs at night and haunted the streets and fields.” Ovid, Fasti II: February 21

The Lemuria (9th, 11th and 13th of May) was a festival to appease the wandering shadows of the dead, lemures, who returned to their former homes and could become a menace if not properly appeased. The shadows of those who had died young were considered to be the most dangerous. Every pious Roman household took measures to protect the home at midnight on the 9th of May:

When midnight comes, lending silence to sleep, and all the dogs and hedgerow birds are quiet, he who remembers ancient rites, and fears the gods, rises (no fetters binding his two feet) and makes the sign with thumb and closed fingers, lest an insubstantial shade meets him in the silence. After cleansing his hands in spring water, he turns and first taking some black beans, throws them with averted face: saying, while throwing: ‘With these beans I throw I redeem me and mine.’ He says this nine times without looking back: the shade is thought to gather the beans, and follow behind, unseen. Again he touches water, and sounds the Temesan bronze, and asks the spirit to leave his house. When nine times he’s cried: ‘Ancestral spirit, depart,’ he looks back, and believes the sacred rite’s fulfilled.

– Ovid, Fasti V: May 9

Tombs of the Dead

Under Roman law, burials were strictly forbidden within the city limits. These laws were not so much the result of religious beliefs or superstitions, but rather a matter of hygiene. The burning of bodies also took place outside city walls because of the threat posed by fire, and because of the unpleasant odour. Consequently, the outskirts of the cities of Antiquity were dominated by necropolises which extended for considerable distances along the main roads.

In the 3rd century BC the use of family tombs was restricted to aristocratic families. These early tombs, following Etruscan traditions, had plain façades and were only decorated on the inside. The tombs were not spacious, and it is not clear whether the ritual ceremonies took place inside or in front of the tomb. Common people were buried in simple shaft graves or terracotta-sarcophagi in large grave fields.

In the 2nd and 1st century BC, more elaborate tombs came into vogue among the aristocracy, and the focus moved from the whole family to the individual. In these centuries, most people were cremated, and the urns containing their ashes were placed in earthen graves or small cists.

During the reign of Augustus, huge columbaria became the usual type of tomb for urns. Several of these can still be seen, such as those in the catacombs along the Via Appia.

In the course of the 2nd century AD, the practice of holding funerary feasts in the tomb became less common, and there is little evidence of cooking or feasting in the later tombs. This was probably due to the increased importance of the collegia, which provided facilities for memorial feasts. Members could also choose to be buried in the collegium’s own tombs or in the tombs of rich benefactors who placed parts of their own tombs at a collegium’s disposal.

There was also a change in how burial chambers were laid out. Important family members were now placed in the main room of the tomb, while slaves and the less important members of the family were disposed of in the cellar. This may have been a consequence of the change-over from cremation to inhumation in the 2nd century AD. Because full size coffins or sarcophagi required far more space than cinerary urns, the inside of the tombs had to be redesigned.

Around a century later, continued pressure on burial space led to the construction of catacombs. The lack of burial places forced some Romans to move their graveyards underground. Catacombs are usually associated with Christian burials, but Jewish and other early catacomb burials have also been found.

Mass Graves for the Poor

Of course, there were some who died poor with no one to pay for their funeral. Corpses were regularly found in the city streets, and the authorities hired people to dispose of the bodies. The bodies were thrown into puticuli, mass graves, which could contain hundreds of corpses, along with animal carcasses and refuse of all kinds.

The archaeologist Rudolfo Lanciani excavated about 75 puticuli in the 1870s and gave an horrific account of his finds:

The Esquiline cemetery was divided into two sections: one for the artisans who could afford to be buried apart in Columbaria, containing a certain number of cinerary urns; one for the slaves, beggars, prisoners, and others, who were thrown in revolting confusion into common pits or fosses. This latter section covered an area one thousand feet long, and thirty deep, and contained many hundred puticuli or vaults, twelve feet square, thirty deep, of which I have brought to light and examined about seventy-five. In many cases the contents of each vault were reduced to a uniform mass of black, viscid, pestilent, unctuous matter.

Beyond Rome - Burial Rites in the Roman Empire

Both cremation and inhumation were practised by the peoples of the Mediterranean region throughout much of Antiquity. The cremation rite, the burning of the body and burial of the ashes, was in widespread use among the Italic and Etruscan people throughout much of antiquity. The Villanovan culture of the Early Iron Age (1100 – 700 BC) north of Rome used cremation, while the southern regions, with their Greek population, preferred inhumation.

The Carthagians, the Phoenicians of the Western Mediterranean, used both inhumation and cremation.

Mummification was the preferred burial rite of rich Egyptians, but most Alexandrians were simply buried. Due to the scarcity of wood, cremation must have been an extremely expensive option in Egypt.

Houses for the dead

Ashes to Ashes

The cremated remains of the dead were housed in urns of many varieties and shapes. Urns also came in a range of materials; burnt clay, metal, glass and stone. The most common type of urn in the Roman era was a simple vessel of fired clay with a lid, called an olla. This cinerary chest is a typical late Etruscan chest of burnt clay, decorated with a frontal relief. These Etruscan chests, which were often mass produced using moulds, were put into niches in the walls of long, rock-hewn passages. The niches were closed with large tiles.

Glass urns were quite costly and came in several varieties. The glass urn is a type that was common in the north-western provinces of the Roman Empire. Another type of cremation urn used by Rome’s neighbours was the amphora. The vast necropolises of Carthage show that cremation burials in amphorae have a tradition dating back to around 800 BC. This is an example from Sousse in Tunisia. These small amphorae were not used as storage vessels, but were specifically made for use as funerary urns.

In Alexandria, urns were placed in vast catacomb-like underground necropolises. A large number of urns made of Egyptian alabaster and granite have been found in Rome, one of many testimonies to the lively trade between Egypt and Italy. These imported urns must have been luxury goods, which only wealthy Romans could afford. This urn was found in the Roman city of Tusculum, south-east of Rome (today’s Frascati).

Urns and Chests for the Roman Middle Class and Soldiers

Shortly before the reign of the emperor Augustus (27 BC-14 AD), marble cinerary chests with relief became popular with the Roman middle class, and stayed in fashion for the next 200 years. From the inscriptions commemorating the deceased, we see that most of the dead were freeborn, some were members of the aristocracy and others military men. But some were also freedmen, or privileged slaves of important families who had the money and desire for a fashionable burial.

In the second century AD, as many as half of all the customers for these chests were soldiers. Although more and more Romans came to favour inhumation, cremation remained usual in the military camps in the provinces until the 3rd century. Cremation was the obvious choice when a soldier’s remains had to be transported home for burial.

These date from the second half of the 1st century to the beginning of the 2nd century AD, the heyday of this fashion. These rectangular marble chests usually bear decorative reliefs and inscriptions giving the name of the deceased, the length of their life-spans, and the names of relatives who ordered the urn. The formulation “dis manibus” (abr. Dis man or D.M.) means “to the spirits of the dead” and was originally a votive invocation to the spirits of the deceased. It is found on almost all Roman inscriptions, but also on Christian and Jewish inscriptions, which reveals its formalised character.

From Cremation to Inhumation

Although inhumation was not unknown, it was rarely practiced in Rome until the early 2nd century AD when inhumation suddenly gained enormous popularity. The cause of this change is still a great mystery, although many explanations have been put forward. Some are practical – for example, that wood for the pyres had become more difficult to obtain. Others are cultural, and point to the growing enthusiasm for Greek culture which preferred inhumation. Inhumation practices varied according to the financial means of the deceased’s family. The most expensive alternative, affordable only to the very rich, was burial in a decorated marble sarcophagus.

Roman Marble Sarcophagi

Most marble sarcophagi are shaped like a chest. The lid is either flat, or in the shape of a gabled roof. Many sarcophagi have lids where the deceased is pictured reclining on a mattress (Astrup). There were also oval sarcophagi decorated with lion heads. They imitate tubs, troughs and wine presses with lion head spouts.

Myths and Motifs

Many motifs found on sarcophagi have no obvious connection to death. Customers chose scenes or ornamentation according to their personal taste, and only a very few chose motifs that dealt directly with the Underworld or the Afterlife.

Mythological battle or hunting scenes were popular motifs. Scenes of ecstasy and abandon set in a mythical world are also common. The sarcophagus shows such an orgy. We see Amor and Psyche kissing surrounded by a procession of cupids. Depictions from earthly pursuits are also common. A child’s sarcophagus pictures a chariot race, a very popular motif, particularly on children’s coffins, probably illustrating funerary games. The four chariots may have been associated with the four seasons of the year. Perhaps the scene is an allegory; life is a hazardous race, but one that can end in victory.

Dionysos– God of Ecstasy

The god most frequently represented on Roman sarcophagus reliefs is Dionysus, god of wine, ecstasy, feasting and the theatre. He also represented the hope of a bright Afterlife, which explains why he so often appears on sarcophagi. His cortege of nymphs (menads) and satyrs are usually displayed dancing, drinking and making music, symbolised everlasting joy and sexual abandon.

The myth of Ariadne and Dionysus is another popular theme. Dionysus discovered the Cretan princess sleeping on the island of Naxos, and took her as his wife. The story of Ariadne’s awakening from a deep sleep to a new divine existence with Dionysus was probably seen as a metaphor for salvation and life after death. Dionysus is often depicted as drunk with a drinking vessel in his hand, descending from his chariot supported by one of his followers. Other reliefs show him uncovering the sleeping Ariadne.

On the fragment Ariadne sleeps, holding a miniature couple; Amor and a girl with butterfly wings. The girl is Psyche, who was carried to heaven in her sleep by her lover, Amor. A third scene from the Dionysian cycle is his wedding to Ariadne, (NG.S.00464). The fragment depicts Dionysus’ mother, Semele, reclining in a chariot besides an Eros holding a wedding torch.

Centres of Production

There were several important production centres for marble sarcophagi in the Mediterranean world. There was, of course, Rome itself, which alone accounts for about 6000 of the sarcophagi known to us today. Another centre was Dokimeion, a town in Asia Minor, (about 500 known sarcophagi) and Attica, in the region of Athens (about 1500 known sarcophagi). There was also an extensive marked in semi-finished sarcophagi, which were completed at their place of destination. Elsewhere, less elaborate sarcophagi were produced, usually catering for a local market and often imitating the products of the main artistic centres.

Greek workshops are represented by one fragment in our exhibition. The piece is clearly of Attic origin. It depicts a scene from the Battle of Troy. Still visible are the three boat sterns and Greek warriors fighting the Trojans on the beach at Troy.

The piece sawn from the front side of a sarcophagus. It is made of marble from Attica, but could have been made by craftsmen from Crete or Asian Minor. The sarcophagus was decorated with a head of Medusa.

The cupid is a product of a workshop from Asia Minor. Similar cupids can be found on garland sarcophagi from Ephesos on the west coast of Turkey.

The sarcophagus is an example from Palestine, probably from Caesarea. The eagle and garland imitate motifs used by the craftsmen of Attica.

Remembering the dead

Portraits of the Dead

After the burial and all the usual ceremonies have been performed, they place the likeness of the deceased in the most conspicuous spot in his house, surmounted by a wooden canopy or shrine. This likeness consists of a mask made to represent the deceased with extraordinary fidelity both in shape and colour.

– Polybius Histories 6.53)

In addition to inscriptions, the Romans commissioned portraits to commemorate the dead. One type was the ancestor mask, as described by Polybius. Masks were placed in the central hall of the Roman house, the atrium, which served as a reception hall where clients and patrons met. Positioned in such a prominent place, the ancestor masks bore witness to the family’s honourable lineage and served as a strong political statement about the values of the aristocratic Roman family.

In the first century BC, it became quite common to place marble portraits of the deceased in the tombs. Portrait busts or reliefs were set in a niche, or in a frame on the exterior wall of the tombs, giving the impression that the deceased was looking out of a window at the passers-by.

One beautiful example from the middle of the 1st century BC is the bust. It is reworked from a statue, and depicts an old man in a realistic style typical of the art of the Roman Republic. He is dressed in his toga and his aged facial features emphasize his lifelong dedication to his family and the Roman state.

Also common are tomb monuments where the deceased is portrayed reclining on a couch. Our sculpture of a recumbent boy served as the lid of a child’s sarcophagus. The boy’s facial features and hair clearly show that the sculpture was intended to be a portrait of the deceased.

The dead can also be portrayed on a sarcophagus within a circular frame, the so-called clipeus (shield). The clipeus framing the portraits of a couple is held by two winged figures, possibly Geniuses or Victories.

In Memory of a Faithful Friend

Sometimes even animals were given lasting memorials. This gravestone from Asia Minor is dedicated to a dog called Phylokynegos. The rather fat and shapeless old companion is pictured in the upper part of the slab. The lower frame bears the epigram: “My name is Hunting Friend because I once stormed fleet of foot after the terrified animals.”

When the Emperor Died

The death of a Roman emperor was a major event. Emperors became divine after death, and monuments were erected and coins minted in their honour. The enormous cylindrical mausoleums of the emperors Augustus and Hadrian can still be seen in Rome.

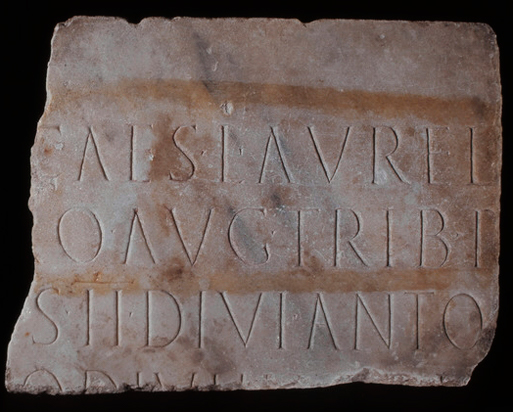

Some emperors, however, were deeply unpopular. In these cases, the emperor’s successor could order that he be treated as an enemy of the state and that all memory of his person be erased; ‘damnatio memoriae.’ This was not a legal order, but nevertheless functioned as very effective public sanction. The rationale behind the practice was that portraits contained a part of the presence of the dead. In ordinary circumstances, placing the statue an emperor in a law court, ensured that justice would be done, while his likeness on a coin guaranteed its value. If, however, an emperor fell out of favour, his portraits, and thus his presence, had to be removed. This was achieved by destroying or reworking statuary and deleting names from inscriptions. This is an inscription to the late Emperor Aurelian (A.D. 270-275). We can also see that someone has tried to erase the name of Emperor Probus (276-282 A.D.), the donor of the inscription.

Once an emperor had been denounced and condemned to a ‘damnatio memoriae,’ he could be denied a proper funeral. Suetonius writes about the makeshift burial of the hated emperor Caligula, who was murdered by leaders of the Praetorian guard.

His body was conveyed secretly to the gardens of the Lamian family, where it was partly consumed on a hastily erected pyre and buried beneath a light covering of turf; later his sisters on their return from exile dug it up, cremated it, and consigned it to the tomb. Before this was done, it is well known that the caretakers of the gardens were disturbed by ghosts, and that in the house where he was slain not a night passed without some fearsome apparition, until at last the house itself was destroyed by fire.

– Suetonius, Caligula 59.

A Fate of Nature: Pompeii

Perhaps the most famous of all „necropolises“ of the ancient world is the city of Pompeii. Pardoxically, this „burial place“ is not the work of man but the result of the violent forces of nature. In the afternoon of August 24th 79AD, the volcano Vesuvius erupted and within days, Pompeii and nearby Herculaneum were destroyed, buried under thick layers of pimpstone and ash. An estimated 5 000 people died as a consequence. Some were buried under collapsed buildings or were struck by flying volcanic debris. Others died from the intense heat and poisonous gases generated by the erruption. Some have been preserved at their moments of death by forces that killed them.

Cultural Crossroads – the Roman Provinces of Syria and Judaea

The region comprising present-day Israel, Palestine, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria has been known by various names; Canaan, Phoenicia, ash-Sham, Assyria, Philistia, the Holy Land, the Levant, the Near East and the Middle East. The problem of finding a common name for this area reflects its rich and complex history, the traditions of the many peoples who have lived here, and the conflicts that have taken place. We have chosen to use the terms the Romans used - the Province of Syria and its sub-province Judaea - and our focus is on the period of Roman occupation – c 64 BC to c 600 AD.

The area was then, as now, home to many religions and groups of people. It was inhabited by the Nabateans in the south with their desert capital Petra, as well as other Arab tribes in the deserts. There were cosmopolitan centres like Antioch in the north, the Decapolis cities in the east and the prosperous caravan oases, Palmyra.

With its seaports and caravan stations, Syria/Judaea was a major crossroads for the trade routes of Europe, Asia and Africa. The area’s inhabitants were mainly Semites (people who speak Semitic languages like Aramaic, Arabic or Hebrew), but people from all over the Greco-Roman world also settled here. Some were Roman officials and soldiers stationed in the Provinces. Others came to take part in the region’s booming trade and commerce.

Syria/Judea was the home of many cults and religions. The traditional Greco-Roman gods were worshipped by the Romans and Greco-Roman communities and there were numerous polytheistic sects and cults of Arabic, Persian, Egyptian, Mesopotamian and Aramaic origin. There were also the monotheistic religions; Judaism and Christianity. The rapid spread of Christianity greatly reduced the area’s religious diversity and by the 5th century, only the Jewish community survived intact as a distinct minority within the Christian Eastern Empire.

A Roman Province

The Romans first began to occupy Syria around 64 BC, and their control over the whole area was consolidated by the end of the 1st century AD. Roman authority did not go unchallenged; a Jewish revolt against the Romans (66-70/73 AD) ended with the destruction of the temple in Jerusalem in 70 AD. Later, in 132 AD, the Jews launched the Bar Kokhba revolt, which aimed to free Judaea from Roman rule. By 135 AD, the revolt had been crushed, leaving over one thousand towns and villages devastated. Hundreds of thousands of Jews were killed, deported or sold into slavery. The Jewish religion was suppressed and the Jews were banished from Jerusalem.

Around 250 AD, the oasis town of Palmyra grew rapidly and soon became one of the most powerful towns in the area. But when Palmyra’s Queen Zenobia conquered Egypt, and began attacks on Asia Minor, the Emperor Aurelian led a counterattack. Palmyra was defeated and ultimately destroyed in 273. The Sassanids, who reigned in Persia, attacked Syria repeatedly after 240 AD and gained control of the area in the early 7th century. In 636 AD, the Arabs conquered Syria, marking the end of Classical Antiquity.

The Burial of a Soldier´s Family in Roman Jerusalem

Lead sarcophagi were quite common in the Mediterranean area, as they were probably much cheaper than stone sarcophagi. In Roman Syria and they were used by many groups, including Romans, Jews and Christians.

We have several indications that the lead sarcophagusbelonged to a Roman legionary family. It was found in Jerusalem in a rock-cut shaft, covered with two layers of stone slabs. The shafts had been dug and used for earlier burials, as skeletal remains were found under our sarcophagus. The sarcophagus had been lowered into the older grave-shaft without removing the former occupant. Our burial contained the skulls of two children about four and ten years old and some pieces of jewellery. A second sarcophagus in a parallel shaft contained the skeletons of two adult males. Pieces of jewellery found outside the coffins had presumably been placed on top them by the mourners.

Lead sarcophagi were made of lead sheets that were cast in clay moulds and soldered together. Decorations were made with wooden stamps pressed into the moulds when soft. The decoration on our sarcophagus depicts Minerva with her owl set in a frame with the shape of a clasp of a Roman breast plate. This motif suggests that the men had military backgrounds. Perhaps these are graves of legionaries and their families stationed in Colonia Aelia Capitolina, (Roman Jerusalem), where the Legion X Fretensis was stationed until the 3rd century AD. This hypothesis is strengthened by the fact that some of the grave gifts are of types rarely found in Roman Palestine, but common in other parts of the Empire.

The Decapolis and Palmyra – Cosmopolitan Cities of the East

The Decapolis – League of Ten Cities

The Decapolis, the league of ten cities, was an alliance formed to protect and defend the Roman Empire against enemies from the east. The heartland of the Decapolis included today’s north-western Jordan, north-eastern Israel, north eastern-Palestine, and south-western Syria. The member cities changed from time to time, and included Skythopolis, Gadara, Pella, Philadelphia, Abila and Gerasa. What characterised Decapolis cities was that they were strongly influenced by Greek and Roman culture and enjoyed a high degree of autonomy, in an area otherwise dominated by Semitic peoples and traditions.

Many tombs from the first two centuries AD can still be seen in the Decapolis area. They were hewn into the rock and consisted of one or more burial chambers. From these chambers, long shafts (loculi) for the burials extended into the walls. After the body was placed in the loculus, the opening was sealed and covered with plaster. The shafts could be used several times by reopening and closing the entrances.

The grave busts in our exhibition come from tombs from the Decapolis cites of Gadara and Skythopolis. Unfortunately the tombs in these towns have been looted, but excavations of similar tombs from neighbouring Abila indicate that busts were places in front of the loculi, probably on the chamber floor.

Nefesh

In his work on the pre-Islamic religion of the Arabs, the Arab historian Hisham Ibn-al-Kalbi (747 – 819/821 AD) gives us a hint as to how these statues might have been used,

Thereupon he carved unto them five statues after the image of their departed relatives, and erected them over their graves. Then it came to pass that a relative would visit the grave of his brother, uncle, or cousin, whatever the case might be, pay his respect to it, and walk around the statue for a while. (Kitab al-Asnam Al-Qalis 44-45):

This suggests that the images of the deceased were used in a dancing or walking ritual. But what did they mean to people who erected them?

The term nefesh is important for the understanding of how the afterlife was perceived in the Arabic and Aramaic religions. Originally nefesh meant ‘throat’ or ‘breath’, but it later changed its meaning to ‘life’ and ‘person’, and then to ‘soul’. From the 2nd century onwards, nefesh is also used to mean tombstones and monuments, suggesting that people believed that the soul could become part of the stone, and thus immortal. This idea can be compared to the Roman view that portraits were carriers of a part of the animus or anima of the people they depicted. The busts from the Decapolis region probably served as nefesh, homes for the immortal ”soul” and the embodiment of the deceased.

The earliest of these busts had few, if any, facial features, and only a contour that resembled the upper part of the human body. Busts with more realistic features seem to have developed in the 1st century AD, a time of increasing Roman political and cultural influence. The busts in our exhibition clearly imitate Roman funerary portraits, but cannot be described as such. These are stylised images rather than representations of known individuals. It seems likely that they continued to be used in their traditional role as nefesh, but with a Roman “look,” a good example of cultural fusion.

Palmyra – Bride of the Desert

Palmyra, situated in today’s Syria, was not a Decapolis city, but it was one of the largest centres in the Roman province and an important stop on the caravan route to Persia. The ancient Palmyrian sculpture style is famous, and includes elaborately executed funerary reliefs.

The Palmyrian Way of Death

The vast necropolises of Palmyra contain three kinds of tombs: high towers used for multiple burials, underground burial complexes (hypogea), and temple tombs. The tombs usually contain large burial chambers with long grave recesses in their walls to accommodate the bodies. These shafts were usually closed with decorated stone slabs. Sarcophagi were rare in Palmyra. We know almost nothing about the Palmyrians’ funerary rites or about people’s notions of the Afterlife. Archaeologists have found cooking equipment and food containers which indicate that feasting took place in the tombs. The presence of altars and incense burners also suggest that offerings were made.

Palmyrian Mummies

Rich Palmyrians were usually mummified, a rite known elsewhere in Greco-Roman Syria and Palestine. In Palmyra the bodies were dried without first extracting the brain and intestines as the Egyptians did. The body was tightly wrapped with strips of fine cloth and covered with a thick layer of myrrh paste. A second layer of coarse linen served as stuffing for the outer covering made of fine cloth, sometimes silk from as far away as China. The deceased was also given gifts - coins, lamps, toys, jewellery, pottery, glassware – evidence that the Palmyrians prepared their dead for an Afterlife.

Grave Reliefs

Grave markers were an indispensable part of every Palmyrian burial. As nefesh, they insured the continued existence of the ”soul”. In Palmyra several types of funerary sculpture, and even tombs and monuments, may have served as nefesh.

The most frequent type of funerary sculpture are the relief busts used to seal the grave recesses, loculi. These were produces between the middle of the 1st century AD until the fall of Palmyra in 272/3 AD. The busts themselves are often quite realistic, yet they were clearly not meant to be true likenesses of the deceased. A wide range of motifs - curtains, scrolls, styluses (writing implements), keys, spindles, distaffs, birds, leaves and grapes appear on and around the figure. Their symbolic meaning, however, remains a mystery.

Banqueting Scenes

Banqueting scenes, usually featuring one or two men reclining on a couch surrounded by their family or servants, were also a feature of Palmyrian tombs. Theses sculptures may have been set into niches on the outside of tower tombs or in special compartments inside the tombs.

Five heads from our collection probably once belonged to figures from a banqueting groups. must have been a central figure. His cylindrical cap identifies him as a priest. Other heads are those of typical bystanders. The woman may have been seated at the foot of a couch and the young sons or servants probably stood behind the main figure. These sculptures seem to derive from Greek banqueting scenes and may have served a similar purpose; to mark the wealth and social standing of the deceased.

The Jews

Jewish Funeral Rituals

He that dwelleth in the secret place of the most High shall abide under the shadow of the Almighty. I will say of the Lord, He is my refuge and my fortress: my God; in him will I trust.

91st Psalm

The Jewish population of Palestine, like Jewish communities throughout the Roman Empire, practiced their traditional burial rites. These are described in detail in Talmudic literature, dating from the Roman Imperial- and early Byzantine period.

After death, the eyes and the mouth of the deceased were closed with special care. The house of the family became a house of mourning. Grief was expressed in many ways; people cried and lamented, while others offered consolation to those in mourning. Sometimes earth was strewn on the head, or there was a ritual shaving of the hair and beard. The body was washed, covered with herbs and wrapped in white linen shrouds. The pall-bearers, who carried the body on a bier, recited the 91st psalm on the way to the grave and professional mourners and musicians were often hired to accompany the procession. The deceased was placed into the grave in either just the linen shroud or in a coffin. The tomb would remain open for the three days in case the deceased should wake up, and no services were held in the synagogue in the period between death and burial.

Reburied Bones - Ossilegium and Ossuaries

A type of burial, in which the bones are reburied after the flesh has disappeared, was an important element of the burial rites in many different cultures and periods and is still common today in some parts of Greece, where remains are exhumed after a couple of years, the bones collected and put into chests which are then stored in charnel-houses.

The rite was practised in Palestine as early as the 1st millennium BC, when human bones were placed in cavities in burial chambers or in charnel-houses, perhaps so that they might also benefit from the offerings made to newly buried. The actual ossilegium, the act of gathering the bones and laying them to rest in a special chest for bones (ossuary) or in niches, began in the last two centuries BC, when the belief in resurrection became widely accepted. A close family member, usually the son, had to collect the bones of his parents one or two years after burial in the family tomb. He would then place them a niche in the tomb or in an ossuary.

Ossilegium has often been seen as a Jewish tradition, but had long been widely practised in the Levant, as well as in Persia and central Asia. It may have mainly served a practical function, as burial space was scare and expensive in densely populated areas, Ossilegium provided an acceptable way of clearing away older burials, and making room for new ones.

Although ossuaries may not have been a Jewish invention, the tradition became a popular one. Ossuaries came in vogue in about 20 BC in Jerusalem, about the same time as marble cinerary chests became popular in Rome, and provided wealthier Jews with a fashionable funerary container much like those used in other parts of the Hellenistic-Roman world.

This is a beautiful example of an early Jewish ossuary, from the period 20 BC to AD 70. The ossuaries were often made by makers stone masons, which may explain their frequent use of architectural ornaments, such as the six-petalled rosette.

Diaspora

Originally ossuaries were only produced in Jerusalem and its surrounding region. After the destruction of Jerusalem in AD 70 following the first Jewish revolt, the production and use of ossuaries shifted to other parts of Palestine, probably due to the movements of Jewish refugees in the Diaspora.

Some 50 years later, the Bar Kohbar revolt (AD 132-135), led to further oppression and the expulsion of the Jews. Families were forced to leave their homes, thus making the maintenance of their family tombs difficult, if not impossible. One solution may have been to transport the bones to the family tombs in light wooden chests instead of heavy stone ossuaries. (C 40839; 40840)? (finnes ingen foto; her er det 2 nr, men 1 tekst)

The Jewish Necropolis of Jaffa

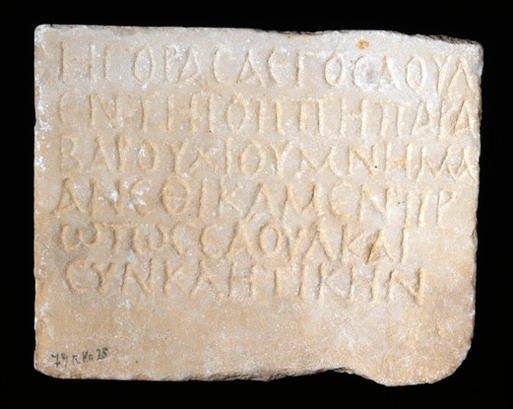

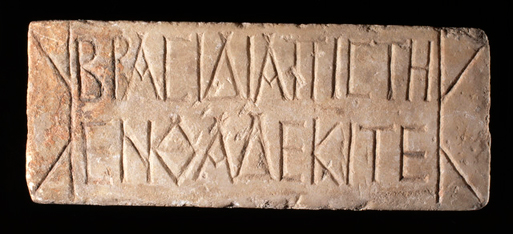

After the expulsion of the Jews from Jerusalem and parts of Judaea, only a few places in Palestine still had sizeable Jewish communities. We know of several minor Jewish burial sites from Late Antiquity, but only two larger ones. Both of these are situated on the coast, at Beth Shearim and Jaffa. Our collections contain a significant number of the surviving inscriptions from the necropolis at Jaffa.

Because of the extensive looting that took place at this site in the late 19th century, the individual tombs can no longer be dated using the grave goods they must once have contained. We can estimate that the necropolis was in use some time between the 3rd and the 5th century AD, and recent excavations and descriptions by 19th century travellers provide us with some information about the appearance of the tombs. About 50 tombs have been excavated and more than 80 tomb inscriptions are known.